Security Lessons from The Israeli Trenches

By Thomas H. Henriksen

A half-century of counterterrorism

Reflecting on last summer’s Hezbollah-Israel border conflict reminds us just how long the Jewish state has had to fight for its existence against enemies that have now become our foes. American practitioners of counterinsurgency have too often studied the lessons of U.S. forces in the Vietnam War or the British in Malaya while neglecting the very relevant experiences of the Israel Defense Force over the past several decades in combating terrorism and insurgency.1 Located in the heart of the Middle East, Israel’s combat theater much more closely resembles America’s challenges in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Horn of Africa in terms of culture, history, and political/religious persuasion than that of communist-inspired guerrillas in Asia several decades ago.

Since its founding in 1948, Israel has faced terrorism, insurgencies, and attacks from sub-state actors operating with non-Western goals and values, along with conventional wars and existential threats from aspiring nuclear nations such as Iraq and Iran. Israel’s versatility and adaptability in successfully combating threats not only has defended the survival of the embattled nation but also has made it an intriguing case study. As such, the Israel Defense Force’s military actions have been — and are — a laboratory for methods, procedures, tactics, and techniques for the United States, which now faces the same Islamist adversaries across the planet.

These long- distance Israeli strikes should have served as a model for what would be required of the United States.

Years before the United States launched its retaliatory airstrikes on Qaddafi’s Libya, al Qaeda camps in Afghanistan, or the al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant in Sudan, Israel had staged commando raids and counterstrikes against terrorist networks and sovereign states that facilitated their assaults. It conducted a contemporary version of the international preemptive strike when its Air Force famously destroyed Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981 after a failed Iranian air force effort to accomplish the same goal the previous year. Although Operation Babylon initially elicited international opprobrium, it was later judged beneficial to halting Iraq’s nuclear ambitions. In 1985, the iaf mounted another less well-known long-distance airstrike necessitating midair refueling against the Palestine Liberation Organization headquarters south of Tunis. This attack eliminated several key plo figures.

These long-distance Israeli strikes should have served as a model for what would be required of the United States. The extended-range hostage rescue by the Israeli Defense Force at Entebbe airport in July 1976 preceded a similar but unsuccessful American foray into Iran just four years later. In the Israeli case, terrorists hijacked an Air France commercial jet bound for Paris from Tel Aviv, after a stopover in Athens, on June 27, 1976, and rerouted it to Uganda. Upon reaching Entebbe, the four hijackers — two from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and two from West Germany’s Baader-Meinhof gang — enjoyed the collaboration of Ugandan President Idi Amin.

Provided intelligence from the idf’s a’man (the Hebrew acronym for Agaf Mode’In), its intelligence branch, the Sayeret Mat’kal (the General Staff’s own reconnaissance commando unit) mobilized, rehearsed its plans, flew 2,500 miles, and struck at the Entebbe airport, rescuing more than 100 passengers and crew with a minimum loss of life.2

But Israel’s dramatic rescue did not serve as a model for the United States. In April 1980, Washington launched its own deep-penetration raid to rescue 52 American hostages who had been seized in the U.S. Embassy takeover in Tehran five months earlier. The spearpoint of the effort called for a mix of Delta Force, Green Berets, and U.S. Army Rangers. Despite lengthy preparations, the 600-mile flight ended in disaster at its Desert One rendezvous when three of the Sea Stallion helicopters mechanically broke down and a fourth was destroyed in an accidental crash at the site. The costs also included eight U.S. lives, captured documents revealing the names of Iranians willing to help the rescue team, and an American humiliation.

To be sure, not all Israeli operations have ended so happily or mythically as the Entebbe venture. Palestinian groups have ambushed idf patrols, rained rockets down on Israeli civilians, and killed bus riders or café-goers with suicide bombs with regularity. But in its grinding counterinsurgency operations and its counterterrorist sweeps, Israel’s missions could furnish abundant lessons and even warnings for American strategists willing to observe and profit from them.

Israeli operations

A bit of historical reflection on Israeli experiences is instructive. Not long after its Independence War, the new country underwent the first of the terrorist attacks by irregular fighters that endure to this day. These intruders came from across Israel’s borders. From guerrilla training camps in the Sinai Desert or the Gaza Strip, Egyptian intelligence officers trained Palestinians whom they recruited from refugee camps. Starting in 1964 with the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organization, terrorist infiltrations also picked up from Jordan. The attacks soon caused hundreds of Israeli deaths.

At first, idf units engaged Palestinian infiltrators and even Jordanian troops in head-on firefights. Later, Israel employed defensive measures, such as clearing vegetation that concealed terrorist movements, implanting mines, and erecting electronic fences monitored by closed-circuit tv cameras. The Israelis also inserted Arabic-speaking intelligence and undercover operatives into the Palestinian population to expose and break up terrorist cells.

The combination of active and passive measures complicated the plo intrusions, though it did not completely halt them. But more than enough interceptions took place that a genuine people’s war never took root among the occupied Palestinians living in the West Bank. Therefore, though young men, and sometimes women, in the West Bank towns stoned Israeli security forces, as in the first intifada, they did not pose the same danger as those launching rockets or ground attacks from Lebanon or Gaza. This noteworthy measure of more or less closing a porous border to the flow of men and arms necessary to sustain an insurgent uprising warrants careful study by other military forces facing a similar challenge.

Lessons also can be gleaned from Israeli counterterrorist operations in the Gaza Strip. Here, squads of soldiers functioned more as policemen and detectives than as combat infantrymen. Formally under Egyptian control, Gaza, along with the West Bank, fell to Israel during the 1967 war. Israel ruled directly but strove to permit Gazans to live normal lives, engage in commerce, work within Israel, and receive public services. Although they resented Israeli rule, Gazans experienced economic improvements in their daily lives, something that the anti-Israel guerrillas determined to disrupt in a preview of post-Saddam Iraq.

Among this population operated some 800 terrorists within Yasir Arafat’s plo and George Habash’s Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (pflp), which funneled in money, arms, and trained cadres from Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria through Egypt. The plo and pflp established underground cells, recruited young men, staged attacks on the idf, killed suspected Israeli collaborators, and generally destabilized Gazan society through torture, murder, and intimidation. As is typical in most guerrilla wars, violence hit the civilian population hardest in order to block cooperation between it and the government. Operating in the teeming refugee camps or thick orange groves, the plo and pflp enjoyed classic advantages of elusive guerrillas in cover and evasion from easy detection by Israeli counterinsurgency forces.

In the teeming refugee camps and thick orange groves, the PLO and PFLP eluded detection by the Israelis.

In 1971, Major General Ariel Sharon, commander of Israel’s southern zone, turned his attention to Gaza’s mushrooming insurgency. General Sharon hit upon a unique method of subdividing Gaza and crippling movement and communication among terrorist units: He assigned squads of elite soldiers to each zone, in which they were to learn intimately the paths, orchards, houses, and other features as well as the routine comings and goings of the inhabitants. Anything out of the ordinary aroused their interest and possibly their deadly response. Dressing soldiers as Arabs, planting undercover squads, turning captured terrorists into agents, the idf generated intelligence that led to dead or captured guerrillas.3

Incessant cross-border mayhem necessitated aggressive Israeli intelligence-gathering. Paid Arab informants, while sometimes useful, constituted only one type of intelligence and required time and effort to verify validity. The Israelis decided on using special military units not just to execute deterrence raids based on intelligence gained from other sources but also to initiate operations to obtain intelligence. They operated on the principle that he who waits in counterterrorism is lost. Thus, in the mid-1950s, Israeli authorities lifted a page from one particular World War ii-era platoon of the pal’mach (units sanctioned by the British to wage guerrilla war against German forces): the Arab Platoon. Made up of Middle Eastern Jews who could speak and pass as Arabs, the Platoon insinuated agents into Transjordan, Lebanon, and Syria to conduct irregular warfare and to gather intelligence. Disbanded by the British near the end of the war, the Arab Platoon concept lay dormant until the 1950s when Israeli special forces resurrected units and undercover agents, which later functioned within the hyper-tense environments of the West Bank and Gaza territories. Unique to Israeli forces among Western armies, the idf deliberately conducted military actions to flush out intelligence along with their retaliatory and deterrence ends.

Unlike the modus operandi of pre-9/11 U.S. Special Operations Forces, which had an “intel-drives-ops” approach, the Israelis utilized a cyclical posture of operations feeding intelligence feeding more operations. Intelligence-seeking operations are now more frequent in the American special-ops community, but they are still not a staple of military actions. America’s forces often lack enough “actionable intelligence” in Iraq. The dearth of Arabic language skills, reliable human intelligence (humint) from trustworthy agents, and the symbiotic integration of collection with analysis and operations keeps us far behind needs. Many Israeli company-sized regular army units include an Arabic-speaking interrogator to access information quickly so as to preempt terrorist attacks. Civilian and military officials frequently make a point of emphasizing the centrality of humint to Israel’s defense.4

In self-defense, Israel also reintroduced into contemporary usage the technique of targeted killings, although its governments have often disclaimed responsibility for specific attacks on terrorists and provided no official statistics on the number of deaths.5 The practice of targeted killings has ebbed and flowed with the intensity of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The methods involved have also varied with the circumstances and include booby-trapped packages, helicopter gunships, f–16 fighters, car bombs, and commando operations. Helicopter fire, for instance, eliminated Sayyed Abbas Musawi, the Hezbollah secretary general, in 1992. One ingenious method saw the use of a booby-trapped cell phone in January 1996 that exploded to kill Hamas member Yahya Ayyash, known among Palestinians as “the engineer” for his bomb-making expertise. One authority on Israeli responses to terrorism credited the assassinations of two key Egyptians in the 1950s with the suspension of Egypt-based fedayeen raids for ten years, thereby demonstrating their early effectiveness against cross-border assaults.6 Possibly the best-known counterattacks took place against perpetrators of the slaughter of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. In a series of preventive strikes to block further massacres, Mossad agents undertook 13 killings against the Black September movement, an amorphous branch of Fatah, which is the largest plo organization.7

Israeli authorities stepped up targeted killings in response to the number of attacks on the country’s civilian population with the outbreak of the second intifada in fall 2000 after the collapse of the Camp David negotiations. Palestinian terrorists intensified their suicide attacks against Israeli civilians. The Palestinians’ increased use of suicide bombers also changed the calculus of the uprising. Hence, the second intifada witnessed a drastic change in the ratio of Jews killed to Palestinians, reaching 1 to 3, whereas in the first intifada it had been 1 to 25.8

The frequency and mode of Israeli counterattack also changed substantially during the second intifada. The Israelis eliminated many mid-level facilitators of Palestinian terrorist organizations. In 2001, more than 20 were reported killed by snipers or helicopter gunships in what the Israeli government termed, in its Hebrew phrasing, “targeted thwarting.” The majority of those eliminated have been second-level terrorists, except for Mustafa Zibri, the pflp secretary general, and Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the main leader of Hamas, who ordered most of the suicide bombings that killed over 1,000 Israelis during the second intifada.

The counteroffensive did reduce the organizing and execution of terrorist bombings on Israeli civilians. Given the near impossibility of defending countless terrorist targets in streets, restaurants, airports, bus stations, and other public sites, preemption of attacks is the only reasonable deterrent measure.9 The Israeli government frequently notified the Palestinian Authority of those on its list for terrorist activities. If the pa failed to arrest the terrorist organizers, or, as often happened, alerted them instead, then the idf put them in its gunsights.10

U.S. targeted killing operations

America’s use of targeted killings has lagged behind that of the Israelis despite many provocations. There are two broad explanations for America’s hesitancy to act. First, despite a spate of terrorist attacks on American officials, citizens, and military personnel stretching back over three decades, the United States argued it could not strike back due to an absence of actionable intelligence on those responsible. Second, in the past the U.S. remained wedded to conventional diplomacy and security arrangements rather than utilizing unconventional means to combat terrorism. Even after Hezbollah murderers drove a truck bomb into the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983, killing 241 American troops, the Reagan administration never acted on a planned bombing mission against one of the group’s training camps in Lebanon. Some in the administration worried about the cut-and-run approach of withdrawing U.S. forces months later. Secretary of State George Shultz prophetically called for action beyond “passive defense” to include “preemption and retaliation” in a speech at the Park Avenue Synagogue in Manhattan in October 1984.11 That advice helped precipitate a limited air attack by Ronald Reagan against Libya two years later.

The first successful, acknowledged application of post-9/11 targeted killing tactics was in Yemen, not Iraq.

After the Qaddafi near-miss, the United States made a second attempt at a targeted killing in 1998 against Osama bin Laden for his role in the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, which killed 12 Americans and hundreds of Africans. Acting on intelligence placing bin Laden and his inner circle at a camp near the city of Khost on August 20, U.S. naval vessels in the Arabian Sea launched 79 Tomahawk missiles that slammed into both the Afghan terrorist installations and the al-Shifa plant near Khartoum. Operation Infinite Reach killed an estimated 20 to 30 people in the training camps and demolished the Sudanese chemical plant, which was linked to al Qaeda. But bin Laden and his top lieutenants escaped the strike, having perhaps been tipped off by Pakistani intelligence.

The first successful, acknowledged application of post-9/11 targeted killing tactics turned out to be in Yemen, not Iraq. The cia fired a lethal missile and killed an alleged associate of bin Laden and five suspected al Qaeda operatives in the first days of November 2002. An unmanned Predator drone unloaded its deadly five-foot-long Hellfire rocket straight into a vehicle carrying Qaed Salem Sinan al-Harithi, a suspected al Qaeda leader and an accessory in the U.S.S. Cole bombing, as he and his driving companions drove 100 miles east of Sanaa, the Yemeni capital. This time Washington justified the threshold-crossing assassinations because the traveling party was considered a military target — combatants — under international law.

Other targeted killings followed. Nineteen months later in the tribal agency of Pakistan’s South Waziristan, another al Qaeda-linked leader, Nek Mohammad, met a similar fate by a laser-guided Hellfire from a pilotless Predator. In a strike on January 13, 2006, it was reported, cia agents fired missiles from a Predator on a mud-brick compound in Damadola, Pakistan, targeting al Qaeda facilitators. The airstrike reportedly killed Abu Khabab al-Masri (Midhat Mursi al-Sayid Umar), who had trained al Qaeda fighters in chemical and biological explosives, and Abu Ubayda al-Misri, who had headed insurgent operations in the southern Afghanistan province of Kunar, among others. An even more spectacular application of taking down a jihadi terrorist came with the death of the notorious Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in a safe house north of Baghdad on June 8, 2006, when two f–16 jets dropped 500-pound precision bombs.

Despite the apparent adoption of Israeli defense tactics, the United States has resorted only to missile strikes or aerial bombardments in its targeted killings. And these have taken place far beyond U.S. borders. It has not succeeded — at least publicly — in commando raids with the specific mission of shooting to death a known terrorist residing within a country that enjoys de jure peace with the United States. Israel, on the other hand, has undertaken several such operations. Among the most notable was a special operations removal of Abu Jihad (Khalil al-Wazir), a Yasir Arafat loyalist and deputy plo commander, who oversaw numerous terrorist assaults with many victims. Operating from Tunisia, Abu Jihad made for an elusive target. An elaborately planned assassination operation involving the Mossad, naval special forces, and the iaf was carried out in 1988 by Sayeret Mat’Kal, which infiltrated a posh suburb of Tunis.

The Clinton administration discussed at length whether Special Operations Forces should be sent either to try to capture or to kill Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan in the late 1990s, but nothing came of the deliberations, hence possibly losing an opportunity to remove the terrorist mastermind before the 9/11 attacks. The Clinton White House desired to escape the blame if a subsequent investigation construed an authorizing memo as a shoot-to-kill order from the president.12 The Israeli elite secret units proved far bolder in their raids because, in part, they enjoyed the backing of their political leaders.

Lebanon: Invasion, Counterinsurgency, Withdrawal

Just as anti-israel terrorism anticipated attacks against Americans, so also did Israel’s nearly two-decade battle with the intractable insurgency in Lebanon eerily presage U.S. experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan. Rather than fixating on the lessons of the Vietnam War, American students of war would have benefited from looking at Israel’s incursions into Lebanon during the 1980s and 1990s. They might also have gained insights and warnings of unanticipated resistance in the post-invasion phase following the “shock and awe” offensive in the Iraq War. An ounce of anticipation would have gone a long way toward adequate preparation for America’s largest counterinsurgency enterprise since the Vietnam War.

The Israelis helped Lebanese civilians cross over into Israel for sanctuary, food, work, and medical treatment.

By the late 1970s, southern Lebanon had erupted as the primary Arab-Israeli battlefield. The plo and pflp had established bases there after being forcibly expelled from Jordan. Before actually occupying southern Lebanon, Israel made repeated armed forays into the adjoining borderlands as retribution for and deterrence against Palestinian assaults. Another part of the Israeli strategy embraced the so-called Good Fence policy that provided security while enabling Lebanese civilians to cross over into Israel for sanctuary, food, employment, and medical treatment. As such, it represented a quasi-“hearts and minds” campaign to win over anti-plo elements and to stabilize the southern reaches of Lebanon. This objective coalesced in a major nonmilitary effort to bolster a population friendly to Israel. Despite the efforts of the idf and its local Christian-Shiite allies, the plo persisted in firing Katyusha rockets, lobbing mortar rounds, and launching terrorist attacks from Lebanese soil.

These deadly assaults made Lebanon a virtual national obsession among Israelis and led to a large-scale conventional invasion of the coastal country on June 6, 1982, in Operation Peace for Galilee. Six and a half Israeli army divisions pushed deep into Lebanon, seizing more than a third of the country (almost to the Beirut-Damascus Highway that bisects the nation) by the time the first cease-fire went into effect. The conventional phase of this blitzkrieg intervention largely succeeded in sweeping most plo guerrillas back from the southern border.

The Lebanon incursion attained one of Israel’s goals at the end of August, when the plo agreed to evacuate Beirut under a U.S.-brokered agreement to spare the seaside capital from further destruction. Nearly 15,000 plo fighters and their dependents departed for Tunisia, and others went to Syria. In time, some plo fighters drifted back to operate in southern Lebanon, however. But the installation of a friendly government, the other main invasion goal, eluded Israel. The resulting instability led Israel to reevaluate its earlier plans for a short-duration occupation of Lebanon and to plan instead for a more lengthy stay so as to protect its northern border. This decision and Israel’s conduct of the resulting Shiite conflict, in the words of one counterinsurgency expert, became “one of the most disastrous chapters in Israeli military history.”13

The invasion and subsequent occupation caused a major political realignment. Whereas the southern Shiite population had originally looked to Israel for assistance against the Sunni-dominated plo, in the 1980s, this community turned against the foreign occupiers. From this resistance emerged Hezbollah (the “Party of God”). The Iran-Syria alliance formed during the 1980s Iraq-Iran War facilitated Tehran’s support of Hezbollah as Damascus became a conduit for Iranian arms, funds, and instructors to reach its co-religionists in Lebanon. The guerrilla warfare and terrorism that soon greeted the idf in Lebanon foretold a pattern that U.S. and coalition forces would encounter in Iraq. A long porous border with a hostile Syria also foretold what would befall U.S. forces in Iraq after the 2003 invasion when the American-led coalition faced an adversarial Iran and Syria in post-Hussein Iraq.

The guerrilla warfare and terrorism the IDF braved in Lebanon foretold a pattern U.S. forces would face in Iraq.

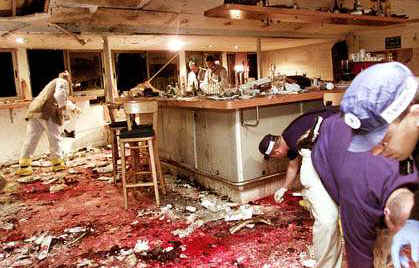

Suicide bombings, later the bane of U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, loomed large early on in the Israeli incursion into Lebanon. In November 1982, a Hezbollah suicide bomber struck an idf headquarters building in Tyre, killing 75 Israeli soldiers. Almost exactly a year later, another Shiite suicide bomber repeated the feat, killing 28 Israeli security officials at the idf/Shin Bet headquarters near Tyre. Between the two attacks, the U.S. embassy in West Beirut was bombed. Even more devastatingly, the American military felt firsthand a Shiite suicide attack when a truck bomber detonated a massive explosion against the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut. These attacks should have served as a red flag to the top civilian war planners in the Pentagon ahead of the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

Over the 18-year occupation, the idf experienced scores of suicide bombings that killed and maimed many of its soldiers as the insurgency spread. Adoption of this tactic by Hezbollah and its military wing, Islamic Resistance, was facilitated by the presence of a 1,500-strong contingent of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, who used it against Iraqi troops during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War. The protracted conflict and the political failure to secure a peace settlement with a friendly government in Beirut led the idf first to a pullout from central Lebanon in late 1982 and then to another pullback in 1985 to a narrow belt of six to ten miles along the Israeli frontier. The smaller area yielded no security for the idf, which continued to suffer roadside bombings and suicide attacks by Hezbollah insurgents taking shelter among the civilian villagers, thus reducing the idf’s advantage in firepower. The idf struck back with helicopter-fired missiles and daring special forces raids to kill or capture guerrilla leaders, but though they were effective they were not on a decisive scale.

After nearly two decades on Lebanese soil, Jerusalem yanked the last of its IDF units out in a disorderly withdrawal in 2000.

The ambushing of thin-skinned Israeli vehicles in southern Lebanon also heralded later trouble for U.S. convoys and patrols in Iraq and Afghanistan. The American-built m113 armored personnel carrier was particularly vulnerable to rocket-propelled grenades and roadway blasts. Nearly two decades after Lebanon, U.S. Army and Marine infantrymen incurred heavy casualties while riding in unarmored Humvees on roadways around Baghdad, Ramadi, and Fallujah until the vehicles were “up-armored” to afford a modicum of protection from smaller explosions.

Israeli popular opinion, like that of other Western societies in similar wars, gradually turned against the protracted Lebanese intervention with its trickle of casualties, well-publicized charges of mistakes resulting in the deaths of innocents, and mounting cost. While Israeli soldiers sustained fewer casualties than their Shiite opponents, the deaths of idf troops had a corrosive political impact in Israeli society. The Lebanon conflict also drained defense resources and demoralized some idf units. Although a series of Israeli governments wanted a settlement with Syria before departing, they were unable to reach accords with Damascus. Finally, after nearly two decades on Lebanese soil, Jerusalem yanked the last of its idf units out in a disorderly withdrawal in 2000. A decade and a half before the U.S. invasion of Iraq, one American analyst perceptively wrote about the idf’s encounter with Hezbollah, saying the “vicious circle of resistance and reaction provides a warning to other states that may become involved in especially sensitive occupations.”14

Although Israel could not impose its political will on Lebanon through invasion and occupation, it did emerge from the quagmire with its northern border initially less violated than it had been before the 1982 invasion. Cross-border attacks were not nearly as frequent as they had been in the pre-invasion period. The reason is that Hezbollah was biding its time to arm and train its forces. Before Hezbollah crossed over the Israeli border in 2006 to capture two idf soldiers and thereby spark the July 2006 war, it had already become a virtual “state within a state” in southern Lebanon. It elected 14 representatives to the 128-seat Lebanese parliament, assumed two Cabinet posts, ran schools and hospitals, and secretly amassed arms and some 14,000 rockets to rain down on Israel with the concurrence of its Iranian patron.

Urban warfare and counterterrorism

Before this past summer’s rocket shower — in fact, a year before Washington unleashed Operation Iraqi Freedom — the idf waged successful counterterrorist operations in the West Bank, undertaking large-scale urban combat operations in April 2002 in several cities, including Jenin and Nablus, as part of its Operation Defensive Shield. As specific case studies, Jenin and Nablus provide useable lessons. The fighting in Nablus’s Kasbah and in Jenin’s Palestinian refugee camp displayed unique features and constituted the biggest military engagements in the West Bank since the 1967 Six-Day War.

Jenin’s Palestinian refugee camp was the second largest in the West Bank. As a consequence of the Oslo Accords, the Jenin camp had come under the Palestinian Authority, which provided civil and security administration in 1995. Cadres from the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade, Hamas, and other terrorist groupings entered the camps and soon orchestrated some 100 suicide bombings during the second intifada. The Israeli government decided to deploy the idf to disrupt the terrorist infrastructure.

In order to minimize civilian casualties in the maze of houses and buildings that made up the crowded refugee center, the idf opted not to use fix-wing aircraft in airstrikes against bands of Palestinian insurgents. The Israelis also worried about giving the “Palestinians the public relations coup of mass civilian casualties” if aircraft bombing formed part of the operation.15

Without an iaf air attack, the insurgent defenders enjoyed two advantages: First, they were spared a devastating aerial bombardment; and second, they knew the intricacies of their urban environment, which would remain largely intact in the absence of Israeli bombing. Flushing out the Palestinian fighters meant going in after them in close quarters. The Palestinians prepared for the idf offensive by laying mines in the roads and booby traps inside buildings. The no-bombs decision also prolonged the siege from an estimated 72 hours to 12 days and increased idf casualties as Israeli troops fought painstakingly, house-by-house, through the 13,000-person camp.

After initial setbacks, the idf threw in giant Caterpillar bulldozers that cleared routes for armored vehicles, pushed aside booby traps, opened fields of fire for advancing idf forces, and demolished houses suspected of harboring terrorists. The Caterpillar d–9, weighing fifty tons and rising twenty feet high, proved particularly effective in safely detonating explosive devices hidden within buildings. Although charges of widespread Israeli massacres turned out to be bogus after United Nations and Amnesty International investigations, the use of the armor-protected bulldozers became a lightning rod for international criticism of idf tactics. As a consequence, the U.S. military ruled out deploying bulldozers during its November 2004 attack on Fallujah. This decision demonstrated that by this late date some U.S. forces were now paying selective attention to Israeli operations. In the course of the Fallujah assault, U.S. forces resorted to artillery attacks and heavy airstrikes on militant positions, leveling whole city blocks. Later, this bombing-induced tabula rasa strategy came in for recriminations and reevaluation as U.S. forces embraced more discriminating approaches.

Inside-out penetration spared Israeli lives and forced the insurgents out into the streets and open areas of Nablus.

Fighting in Nablus also witnessed the novel use of a familiar tactic. Again, to minimize its casualties inside the teeming city, the idf avoided undue exposure in streets, alleys, or courtyards during its infestation by blasting through walls to move horizontally and exploding holes in floors or ceilings to pass vertically within structures. Rather than conforming to old-style frontal assault from block-to-block takeovers, the elite Israeli Paratroops Brigade penetrated the Kasbah district where some 1,000 insurgents awaited them behind elaborate barricades, improvised explosives, and mines buried in streets and alleys. Better prepared than the idf reservists who fought in Jenin, the paratroopers waged a cagey fight in the sprawling labyrinth. Undoubtedly, the inside-out penetration spared Israeli lives and forced the insurgents out into the streets and open areas, where they faced the idf’s greater firepower. Brigadier General Aviv Kokhavi wrote in his battle plan that the defenders faced Israeli troops “swarming simultaneously from every direction.” The idf practice of “walking through walls” rested on extensive research and training. One authority described the method as movement “within the city across hundred-meter-long ‘over-ground-tunnels’ carved through a dense and contiguous urban fabric.”16

The idf did not invent the technique of breaching walls, which has been employed since at least World War ii (and before; sappers have been demolishing defenses since the invention of gunpowder), but it did systematize and employ it on a large scale. Exterior damage was less in Nablus than in the Jenin- or Fallujah-style destruction, and structures were still habitable, although many had holes punched through the walls.

Operation Defensive Shield did not totally eliminate suicide bombs. But the idf reasserted control over the West Bank, which inhibited Palestinian militants from conducting an effective terror campaign. Along with border and civilian police and intelligence agents, it hampered the terrorist underground, using routine and impromptu checkpoints to intercept most suicide bombers bound for Israeli targets.

The sheer volume of idf operations, numbering as many as 700 annually and mounted by squad-sized units, required downward delegation of planning, execution, command, and control. As General Yossi Heymann commented, the antiterrorist effort concentrated on keeping the terrorists on the run and scared.17 The operation tempo dictated “short cycles” between decision makers and the actual operators of countermeasures against terrorism.18 Because of the possibility of unforeseen and adverse circumstances, special forces must anticipate and practice contingency plans. One former idf officer depicted this as the “jazz band” model: Musicians know well the main tune before they improvise on it from operation to operation.19 In Baghdad and other Iraqi cities, U.S. forces now also engage in a surge of search, arrest, and detain operations to throw the insurgents off balance.

Future glimpses

A review of israel’s long conflict with terrorism should serve to remind us that what first happens to the Jewish state often later afflicts the United States. Because Israel’s past has more than once served as a harbinger of our own history, this last summer’s Hezbollah-Israeli fighting should alert us to what we must anticipate. July and August witnessed volleys of short-range unguided missiles, anti-tank weapons used with deadly effect against armored vehicles, and well-trained and disciplined guerrillas indoctrinated, equipped, and resupplied by a militantly nationalistic and nuclear-arming Iran with vaulting ambitions to dominate the Persian Gulf, outflank the Arabs, and head the pan-Muslim world. Given that the Middle East’s past is often prologue, the United States should anticipate a repetition of Hezbollah tactics elsewhere.

As they contemplate reductions of U.S. ground forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, American strategists must envision the next phase in the “Global War on Terror.” In anticipating what methods and operations might become useful, the U.S. military establishment would do well to scrutinize the operations and tactics employed by their counterparts in the idf, as terrorist techniques and adaptations have often been tried out first against Israel.

In the next phase of the anti-terrorist struggle, it seems improbable that in the near term the United States will replicate the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Operation Iraqi Freedom and America’s subsequent nation-building endeavors proved enormously expensive in blood and treasure. Over 3,000 U.S. troops have so far died in the Iraq conflict, and 22,000 have been wounded, many of them severely. In excess of $350 billion has been expended in direct military and rebuilding efforts. Over 150,000 Iraqi fatalities have resulted from the U.S.-led intervention and sectarian killings, although these casualty figures pale in comparison with Saddam Hussein’s atrocities, especially among the Kurdish and Shiite populations. Moreover, the costs of the Iraq War and the initial international furor have restricted American military options against threats from Iran and North Korea. These factors make it unlikely that the United States will soon again embark on another Iraq-type campaign. Yet the gwot shows no sign of winding down. Indeed, the rash of terrorist incidents since 9/11 in Bali, Turkey, Morocco, Israel, Madrid, London, and Mumbai indicate that America’s “Long War” is far from finished. Meanwhile, fragile states such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, Somalia, and Sudan, among others, remain at risk of being turned into the next Taliban haven by Islamic extremists.

The Israeli approach to combating terrorism over the long haul affords an example of a counterterrorism strategy. Given Israel’s limited resources and strategic defensive crouch, it has relied over the years on raids, sometimes fairly long-distance strikes, as prevention, preemption, deterrence, and punishment for terrorism perpetrated on its territory or against its citizens abroad. While pursuing diplomacy and nonlethal measures, the United States might find that it also must dispatch commando raids, capture terrorists for intelligence, assassinate diabolical masterminds, and target insurgent strongholds with airpower, missiles, or Special Operations Forces from bases around the globe rather than undertaking enormous pacification programs and nation-building endeavors in inhospitable lands. Military offensive operations must not be surrendered; they must be applied so as to marshal our resources for a protracted conflict.

1 See, for example, one of the most recent in this genre, John A. Nagl, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam (University of Chicago Press, 2002).

2 Yeshayahu Ben-Porat, Eitan Haber, and Zeev Schiff, Entebbe Rescue (Delacorte Press, 1977), 321–36.

3 Ariel Sharon, Warrior (Simon and Schuster, 1989), 251–62. .

4 In addition to active and retired military officials, Dore Gold, former Israeli ambassador to the United Nations, underlined the importance of reliable intelligence. Interview, Israel (March 19, 2006).

5 For a brief but relatively comprehensive review of Israeli targeted killings, see Steven R. David, “Fatal Choices: Israel’s Policy of Targeted Killing,” in Efraim Inbar, ed., Democracies and Small Wars (Frank Cass, 2003), 138–58.

6 Samuel M. Katz, Soldier Spies: Israeli Military Intelligence (Presidio Press, 1992), 128.

7 For a recent and authoritative account, see Aaron J. Klein, Striking Back: The 1972 Munich Olympics Massacre and Israel’s Deadly Response (Random House, 2005).

8 David, “Fatal Choices,” 141.

9 For a penetrating analysis of the dilemmas posed by targeted killings, see Boaz Ganor, The Counter-Terrorism Puzzle: A Guide for Decision Makers (Transaction, 2005), 128–40.

10 Samantha M. Shapiro, “Announced Assassinations,” New York Times Magazine (December 9, 2001).

11 George P. Shultz, Turmoil and Triumph: My Years As Secretary of State (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993), 648.

12 Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and bin Laden from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (Penguin, 2004), 372–96.

13 W. Andrew Terrill, “Low Intensity Conflict in Southern Lebanon: Lessons and Dynamics of the Israeli-Shi’ite War,” Conflict Quarterly 7:3 (Summer 1987).

14 Terrill, “Low Intensity Conflict in Southern Lebanon.” .

15 Matt Reese, “The Battle of Jenin,” Time (May 13, 2002). .

16 Eyal Weizman, “Lethal Theory,” Roundtable: Research Architecture (2006).

17 Interview with General Yossi Heymann, Israel (March 21, 2006).

18 Interview with Golan Benavi, Israel (March 23, 2006).

19 Interviews with Col. (Res.) Loir Lotan and Hegai Peleg, Israel (March 23, 2006).

Thomas H. Henriksen is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. His current research focuses on American foreign policy in the post-cold war world, international political affairs, and national defense. He specializes in the study of U.S. diplomatic and military courses of action toward terrorist havens, such as Afghanistan, and the so-called rogue states, including North Korea, Iraq, and Iran. He also concentrates on armed and covert interventions abroad.

Copyright © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of Leland Stanford Junior University

Phone: 650–723–1754

No comments:

Post a Comment